You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Sherwood Anderson’ tag.

Tag Archive

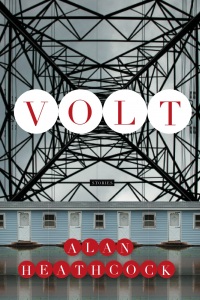

Q&A with … Alan Heathcock

February 21, 2011 in Marketing/promotion, Publishing, Q&A, Reviews, short stories, Writing process | Tags: Alan Heathcock, Alyson Hagy, Arthur Miller, Benjamin Percy, Boise State, Chris Offutt, Cormac McCarthy, Denis Johnson, Emergency, Ernest Hemingway, Flannery O'Connor, In Cold Blood, John Cheever, John Steinbeck, Joy Williams, Joyce Carol Oates, Kentucky Straight, Lord of the Flies, method acting, Novels, Sherwood Anderson, short stories, Taking Care, The Crucible, The Grapes of Wrath, The Road, Truman Capote, Upon the Sweeping Flood, Volt, William Golding, Winesburg Ohio, Writing process | by craiglancaster | 2 comments

In my first question to Alan Heathcock, the author of the forthcoming short-story collection Volt, I used the word “muck” to describe the messes into which he flings his characters.

Popular word, “muck.” Turns out that Publishers Weekly used it, too, in a starred review of Volt:

Heathcock’s impressive debut collection pursues modern American prairie characters through some serious Old Testament muck. If it’s not flood or fire ravishing the village of Krafton, then it’s fratricide, pedocide, or just plain ol’ stranger killing.

Volt comes out March 1st, from Graywolf Press. Heathcock, who lives in Boise, Idaho, and teaches creative writing at Boise State, was kind enough to field a few questions with thoughtful, incisive answers. Enjoy!

The stories in Volt send their characters into some pretty serious muck. What is it about harrowing adversity that is attractive to you as a writer?

The appeal is two-fold. First, I’m what I call an “empathetic writer,” which has kinship to a method actor. I try to become the character in full, think what they think, feel what they feel. The process of writing then becomes an exploration of imagination, intellect, and emotion for me, and putting the characters through the muck is confronting the things that scare and confound me the most. The process of writing has great value to me. It’s not entertainment, but something deeper. I know that sounds pretentious, but it’s as honest an answer as I can give. Second, harrowing adversity simply makes for good compelling drama. Shaekspeare and Cormac McCarthy, two huge influences, put their peeps through deep, deep, DEEP, muck—I, for one, thank them for that.

The appeal is two-fold. First, I’m what I call an “empathetic writer,” which has kinship to a method actor. I try to become the character in full, think what they think, feel what they feel. The process of writing then becomes an exploration of imagination, intellect, and emotion for me, and putting the characters through the muck is confronting the things that scare and confound me the most. The process of writing has great value to me. It’s not entertainment, but something deeper. I know that sounds pretentious, but it’s as honest an answer as I can give. Second, harrowing adversity simply makes for good compelling drama. Shaekspeare and Cormac McCarthy, two huge influences, put their peeps through deep, deep, DEEP, muck—I, for one, thank them for that.

One of the things that struck me in the stories is the sense of time. You provide small clues about the general era of each story, but most any of them could be dropped into any modern decade. Was that intentional?

It was intentional. I was trying to let the stories be as timeless as possible, not having the baggage of a certain period adhere itself to the stories. For instance, if a story is clearly set in World War II a contemporary reader might slap everything they’ve ever read/viewed/heard about that era, changing/warping the intended meaning of the story. I set the stories in a hard “now” time, while leaving the general sense of time open enough so that each story delivers the reader into as pure a thematic reading as possible.

Aside from that, I’m also proposing the simple truth that history repeats itself, that the pains of war and crime and grief must be felt again and again and again. In that respect, time period has no bearing on the truths of humanity.

I read an essay in which you wrote that your stories help you figure out the world around you. What did you mean by that?

Things have happened in my proximity that deeply altered my ability to understand the moral truths I’d been taught in school/church/home. For example, I used to visit a small town in Minnesota named Waseca. I had friends who lived there. It was a lovely little town, nice Main Street, beautiful lakes, kind people. In winter, I went ice fishing, which I loved. In summer, we’d take long walks down these country roads, looking out over the still fields, listening to the locust drone. Then, in 1999, a twelve-year old girl came home from school to find a man robbing her house. The man raped and killed the girl, and her parents found her dead body in the house. I visited Waseca about a month after this happened, and the town had changed. My friends, who used to leave their doors unlocked, now locked their doors and kept a rifle by their bed. Waseca felt changed, the air and water were changed. It touched everything. I couldn’t shake the desire to have Waseca returned to what it was, and wondered what could possibly be done to restore the peace. So…I wrote the story “Peacekeeper” as a means of unpacking some of my questions, a bit of grief, too, trying to see if I could find any answers and heel the troubled mind. Again and again I find myself drawn to questions that plague me, and use story writing as a means to root out any possibly insight that might settle my equilibrium just a bit.

The Volt stories are set in the fictional town of Krafton. Did you model it after any actual place? What does Krafton look like in your head?

Krafton started out as modeled after the small town where my mother grew up: Lynnville, Indiana. But I felt confined by having to abide their grid of streets and knobs and flora and fauna, so I started borrowing from places I’d been in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Kentucky, South Dakota, Idaho… My goal with Krafton was always to just let it be a small American town. I’ve found, via the early reviews, that depending on the reader they place Krafton in different regions (the west, Midwest, great plains, southeast), which is fine with me. So it’s Krafton, America, which enables the commentary to not be bound by region, while adhering itself to whatever region the reader supplies.

Volt is your first book. Are you planning to write a novel-length book, or are short stories where it’s at for you?

I’m working on a novel now, though I’ll keep writing stories. My original idea for these Krafton stories was to write a comprehensive moral history of a town, a collection of 30 or 40 stories covering a town from its founding to its present. VOLT is like volume one of four in a series I hope to eventually complete.

You’re a Chicago guy who’s teaching creative writing at Boise State University. How have you taken to living in the West?

It was quite a transition. The west is vast. VAST. Time and distance are very different in the west. The people aren’t as direct as they are in Chicago. But I’ve grown to completely love the west. Boise, Idaho, is an absolutely amazing place to live. It’s growing like crazy and crackling with energy. In a small way, being part of the growth in Boise connects me with what the pioneers who founded the west must’ve felt, the feeling of being able to effect a place, to put your mark on a land and culture. And the west has some of the world’s most stunning landscape. Idaho is a wonderland of beauty, and beauty hardly touched when compared to everything back east. I’m loyal by nature, but I sincerely love the west, and I’m extremely proud to be a Literature Fellow for the state of Idaho, and Writer-in-Residence for the city of Boise. And everybody back in Chicago hits me up for Boise State football t-shirts and hats—ha. Go Broncos!

Let’s talk process: When do you write? How do you balance it against work, being a husband, being a dad?

We (my family and I) treat my writing like it’s my full-time job, which it is. It teach one or two nights a week at Boise State, and other than preparing to teach I’m working on my writing Monday through Friday, from the moment I get my three kids off to school to the moment they get home. It helps that I don’t have any hobbies (ha). I read, write, watch movies, follow my kids around to all their activities, sneak in a date night with my wife every now and again, and that keeps my life full and productive.

I grew up in a working class area in south Chicago, and I often think of my friends back home who are pipefitters or police officers or office stiffs, who have to go to a job every day, week after week. With them in mind, it’s easy for me to stay disciplined to doing my work—if ever I have the urge to put my feet up on the desk, I just think of them looking in on me, totally disgusted by how soft I’ve become, and that stokes me to get back at it.

What are some of the books that influenced you? Who or what lit your literary fuse and made you want to become a writer?

Lord of the Flies by William Golding, In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, The Crucible by Arthur Miller, the stories of Flannery O’Connor, Ernest Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories, The Grapes of Wrath by Steinbeck, Taking Care by Joy Williams, Upon the Sweeping Flood by Joyce Carol Oates, Emergency by Denis Johnson, the stories of John Cheever, Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson, Kentucky Straight by Chris Offutt, to name a few. But, really, for me, there’s Cormac McCarthy and then all the rest. McCarthy’s books were a revelation to me, were everything in style and story I ever wanted. My top ten books would be dominated by his titles. His novel The Road is the one of a few books I consider to be perfect.

Your publisher, Graywolf Press, has released some great story collections — yours, Refresh, Refresh by Benjamin Percy, Ghosts of Wyoming by Alyson Hagy, among others. How was the publication experience for you?

Graywolf Press is the best publisher out there. Period. I could throw numbers at you to prove it, but if you talk to any author in the wolf-pack, they’ll echo my sentiment. The editors are extremely talented, the sales and promotions crew thorough and dedicated and charismatic. I hear authors published on other presses complain about not being a part of the process, or having quibbles about their book cover or lack of promotions or not being able to get answers from their publisher about this or that. I’ve really felt that with each step Graywolf has included me in the process, cherished my input, given me their best guidance, and championed my book in the marketplace, all with grace and great effect. My book is succeeding both critically and commercially in ways I hadn’t imagined, and I credit Graywolf for enabling that to happen.

As someone who nurtures young writers, what are you seeing from the next generation of storytellers?

I occasionally hear someone lament the lack of imagination coming out of writing programs, but I don’t see it in my classes. I have youngsters writing stories from a myriad of styles and genres, with great variances in thematic content, all with powerful execution. These young writers have grown up with great access to information, have been barraged with stories from around the world, and have been reared in a great time of war and turmoil. They’re filled with stories, brimming with great thoughts and intense emotions. It’s an amazing thing to witness as young writers find their voices and use drama to express their passions in the written word. Time will tell, but I think we’ll see some truly great books in the next ten years or so.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you ever received?

Do not look beyond yourself for validation. Learn your craft to the point you understand the values of quality. Then look inward, and be brave enough to take yourself seriously. The moment you decide to take yourself seriously, to look inward, you will stop imitating others and become original.